Francis Pellerin, the painter

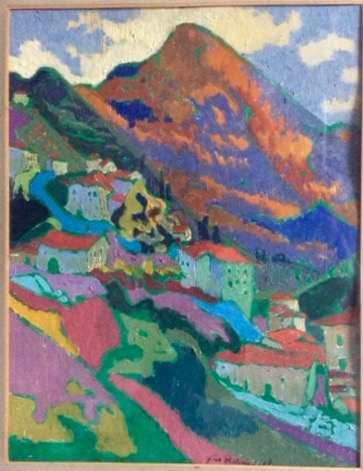

From 1939 onwards, in parallel with his work as a sculptor, Francis Pellerin began to paint; a practice he would continue for the rest of his life. Initially, he painted still lifes, landscapes around Cancale and in the Châteaulin area, and portraits, which remained a subject of exploration for him after he was awarded the Prix Chenavard.

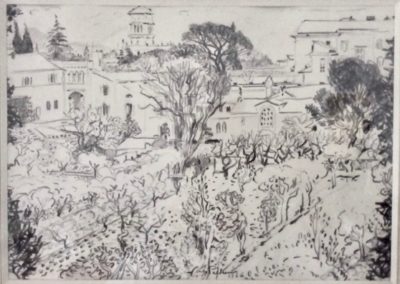

He drew and painted prolifically, in Rome, in Borbona, in Capri, in Sicily, in all the places where sculpture was impossible, but also for the pleasure of it. The works from this period – which lasted until 1951 – enjoyed wide popularity.

In 1952, however, his first abstract painting lost him both his gallery and his buyers, and he suffered the painful experience of depriving his family (by then he and Suzanne had four children) of a livelihood. On the occasion of a Salon des Réalités Nouvelles exhibition in 1960, he wrote:

It is not one’s desire that forges the path of one’s art; the strength which nourishes it leads you where it will. Impelled at first by external nature, I later acknowledged the movement of my internal nature. The result, now, is a sort of symbiosis between the work and the man. The constant is provided by a certain quality of tension. My inspiration is not conceptual. I feel my way; I hope; I must have a lot of faith. A work that cannot be predicted arises from an integration with architecture and from my world. For over 20 years, a concern with polychromy in my sculpture has led me to paint. I became an abstract artist through a logical series of steps; and through architectonic connections, I became a geometric abstract artist. Neither painting nor sculpture fulfil me completely. Because of this, I found what I call “spatial painting” or “sculpto-painting”; a structure which is built up by unfolding itself and, by making use of colour, takes possession of the space and plays with it statically and kinetically.

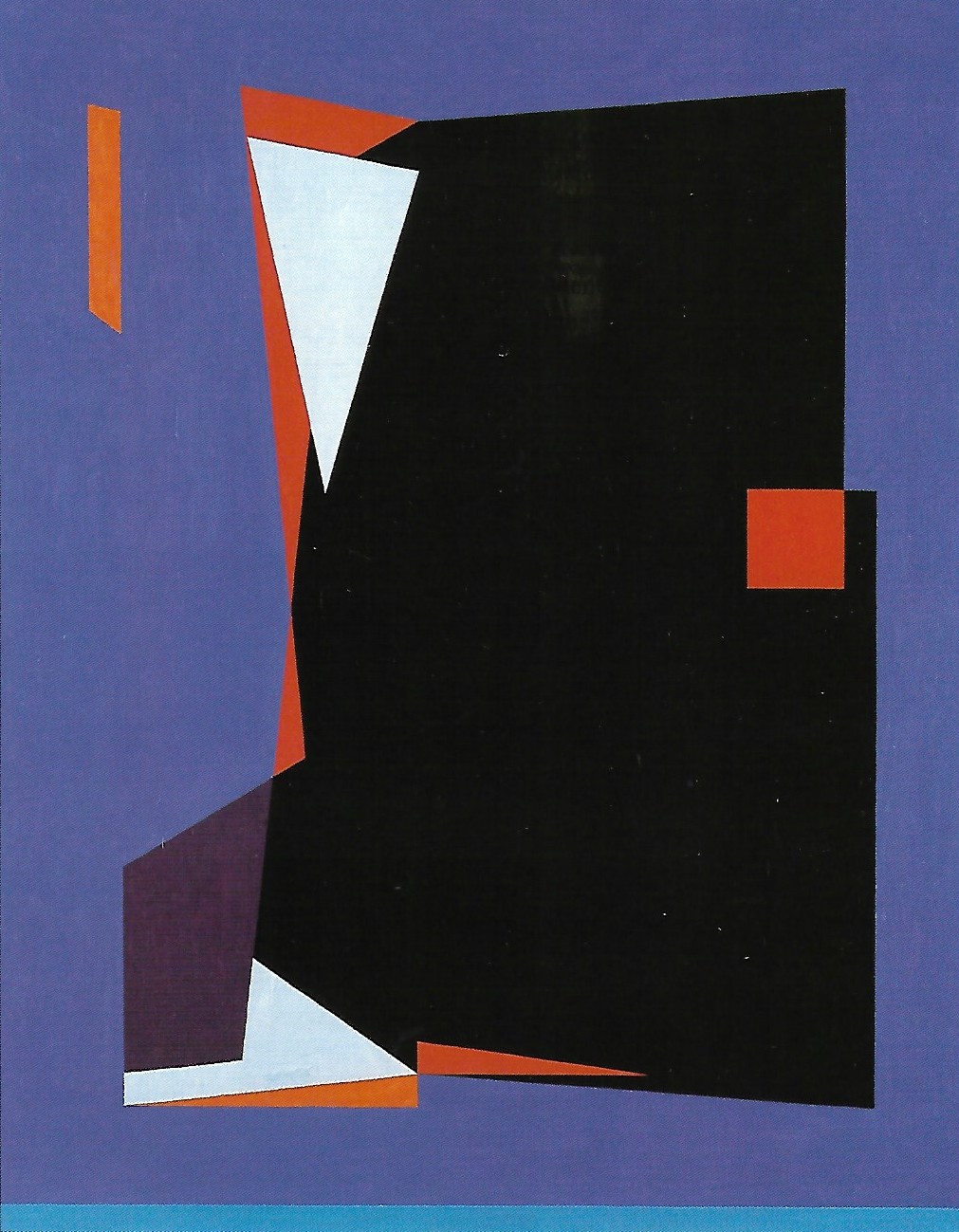

Grand Vaisseau…? A reference to Kazimir Malevich (cf. Note 1) is unambiguous. But why ? Why was this title given by someone who denied himself the pretension of naming his works (pictorial or sculptural, even if he allowed that the viewer may ascribe a name deriving from a personal emotion)? Why acknowledge Malevich, when Pellerin himself wrote in one of his well-known quatrains:

You can see them come

but where should you seek

these forms that you dare

and that arise out of the craft

And then:

Here…How to express it?

This loss of sight

Where things in turn

Find a name only afterwards

Comment 1

“things”, here, has a meaning specific to Arte Madí artists, whom Pellerin encountered and who nourished his creative reflections at a certain point in his career (during the 1950s).

Comment 2

Arte Madí : an artistic movement formed in Argentina in 1946. Madí artists exhibited at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles in Paris from 1948 onwards. The Madí Manifesto stated the exclusion of any “interference by the phenomena of expression, representation and meaning”.

Perhaps Pellerin’s ceaseless artistic exploration and his oeuvre as a whole will enlighten us and provide an answer to the questions asked above. The development and perpetual quest of this “seeker of form” (as he was called) cannot be ignored. Through all his work, in whatever guise it took (monumental and/or polychrome sculptures, paintings, drawings or quatrains), he unremittingly broke with the seen or perceived representation of reality (as it is seen or felt), by means of what he termed “éberluisme”, and also the “apology of pure abstraction” – taking his lead from Malevich. We can also reasonably assume that he saw in the Russian artist and art theorist the willingness to risk pure abstraction (cf. Note 2, however: the move to acrylic). Hence the title Grand Vaisseau, as a tribute to Malevich, given to the four canvases (in oil) executed between 1950 and 1961, confirming Pellerin’s affinity with abstract art. Monique Merly

Note 1:

Quotation by Malevich (1878-1935): …the art of the future as a great vessel moving at infinite speed and sailing beyond the limits of the horizon… (bold format added by author) …the subject is already no more than a pretext, a starting point, the vehicle for a composition that is plastic before all else… (Malevich, 1910)

Note 2:

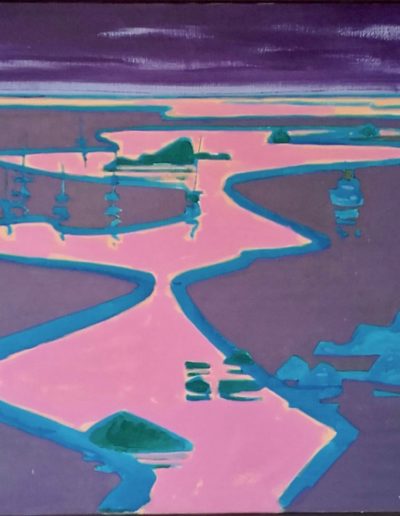

The overall structure of Grand Vaisseau would be the subject of exploration for the artist between 1986 and 1988, resulting in 15 paintings in acrylic, including one from 1988, donated by Suzanne Pellerin to the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rennes.

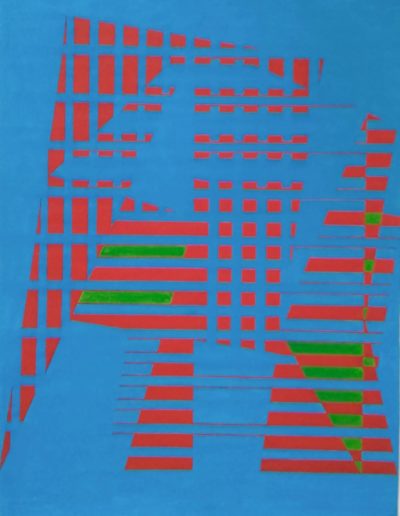

Drawings in ink, regulating lines, extendable structures, paintings in oil, and monochrome and polychrome structures déployées characterise this period with their rigorous and hieratic geometry, prompting Frank Elgar’s observations at an exhibition at the Hautefeuille Gallery in Paris in February and March 1962:

This is an art that is intellectual, sensitive, free, and learned all at once, a form of abstract painting that does not betray the specific laws of the medium, and, between the rigour of the conception and the unforeseen in the execution, strikes the right balance. Neither the austerity of a working drawing, nor the sadness of a pensum is found here. These compositions move, quiver, are alive to the reciprocal actions of their lines and their colours…

Francis Pellerin’s painted work reached a watershed in 1960 with the beginning of his “gestural period”. Works in gouache, some of which were reproduced as tapestries by the Atelier Plasse Le Caisne and the Les Gobelins and Beauvais manufactures, caused his friend Jean Dubois to remark on the occasion of an exhibition:

Confronted with so much movement, life, freedom, one might assume that Francis Pellerin had changed his style. But this is simply a superficial impression. Exuberance is not disorder. The composition, if concealed, is no less real. The line is not as mad as it seems, because it is executed by a hand to which long practice in drawing regulating lines, geometric constructions, has unequivocally endowed a sense of moderation and balance.

In 1972, the chance commission by a private individual who wished for a painting of Capri like the one her daughter owned put Francis Pellerin in front of his easel once again. It acted as a trigger: he would not paint the same landscapes as before, but develop – imbued with the light in Spain, on the Aubrac plateau, in Brittany – a new vision of reality. He would speak of “un regard éberlué”,* expressed in a series of works where the rapidity of execution, made possible by the use of acrylic paint, gives us some astonishing snapshots of a reality laid bare, transfigured by the eye of the painter who often liked to speak of his work thus:

The memory of a memory became so in my soul.

* See the essay published in the Bulletin des Amis du Musée (de Rennes) in 1997 Begotten, Not Created… Joint Reflections and Perspectives on Art. Poems by Francis Pellerin, text by Monique Merly.

He showed this body of work at the opera house in Rennes, calling it Espaces-rêves (Spaces-dreams). See the article by Pierre Fornerod in Ouest-France (18/12/1987).

In the 1970s, Pellerin began to experiment with series of paintings (a transposition onto canvas of what he had been exploring in sculpture for many years?) See Monique Merly’s essay: The Series in the Work of Francis Pellerin, 1982, continued in 2019 with From Abstraction to Kineticism in Painting: Hypotheses.

The works he completed from 1980 onwards display a staggering youthfulness. A great capacity for work and for research led him to unexpected concepts that became more and more refined, freed from the classic identifiers of space. Collages, “accolages” (juxtapositions), drawings, gouaches – all transport us to “spaces of other places” in a state of weightlessness, where we would like to linger.

In the years between 1985 and 1993, Pellerin produced 94 works in acrylic on canvas which represent a return to an abstract geometric style where the regulating line and tripartite composition would slowly disappear.